PLEASE SEE OUR COMPANION HISTORIES

AN INTRODUCTION TO HANCOCK PARK IS HERE

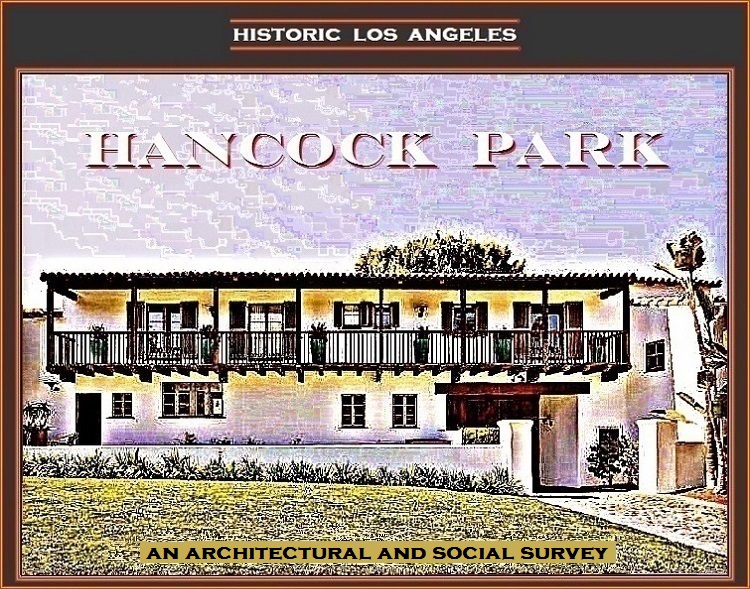

300 South June Street

- Built in 1925 on Lot 146 in Tract 3688 and originally designated as 304 South June Street

- Original commissioner: Harry H. Belden

- Architect: Ray J. Kieffer

- On February 20, 1925, the Department of Building and Safety issued Harry H. Belden permits for a two-story, 12-room house and a one-story, 20-by-30-foot garage at 304 South June Street

- Harry H. Belden was a prolific builder of houses in Hancock Park, Windsor Square, and elsewhere. His Hancock Park houses include 110 North Rossmore, 324 Muirfield, 317 and 624 Rimpau, and 152 North Hudson as well as 12 of the 14 houses on June Street between Third and Fourth streets. Advertisements for Belden-built houses appearing in the Times during November 1925 refer to several residences on the block being under construction; Belden's residences in the 300 block of June Street designed by Ray J. Kieffer are 305, 314, 315, 324, 325, 345, 355, and 356 as well as our subject here, 300. (Belden's projects at 335, 336, and 346 South June were designed by brothers Kurt and Hans Meyer-Radon)

- Attorney Walter Kimple Tuller of O'Melveny, Milliken, Tuller & Macneil—today's firm known simply as O'Melveny—bought 300 South June Street from Harry Belden and may have been the one to have its 304 designation changed to 300; he would also in due course change his middle name as hhe manueuvered himself into domestic chaos

- Walter Kimple Tuller and his wife had five children when they moved to Hancock Park from 337 South Gramercy Place. He'd married Edna May Sheppard of Fullerton in October 1908 months after being graduated from Cal. Living first in San Francisco, the couple settled in Los Angeles after a year. Within three years of moving into 300 South June Street, Tuller found reason to upend his domestic life when he took up with Milwaukee-born Antoinette Ruth Sabel, a former music teacher at Pasadena High School. He divorced Edna May in August 1928; for whatever reasons, it was decided then that the three elder children (Lula May, 18, Carol, 17, and Walter Jr., 6) would be placed in the custody of Mrs. Tuller, who was living in Long Beach, while the two youngest (Mary Louise, 6, and Robert, 4) would live with Mr. Tuller at 300 South June. In 1931 the ex–Mrs. Tuller would be forced by the apparently unrepentant, egotistical, and altogether unpleasant-sounding Major Tuller—he was the pug-faced type of man who clung to a wartime rank well after the Armistice—to plead in court for alimony and for support of the invalid Lula May after her father cut her off at the age of 21; more wrangling over money would occur at the time of his death later in the decade. In the meantime, the Pasadena Post of June 13, 1930, announced that Tuller had married Miss Sabel at the Los Angeles home of friends the day before. A large, rather indiscreet photograph of the couple appeared in the Times on July 10, 1933, as they were embarking on a delayed round-the-world honeymoon. The ambitious new Mrs. Tuller seems to have been very anxious to establish herself socially now that she had the important spouse and more than the salary of a schoolteacher or municipal employee, as she had become. Her husband had been born in flyspeck Iuku, Kansas, on October 6, 1886, as Walter Kimple Tuller (Kimple being his mother's maiden name); it seems that Antoinette preferred the grander-sounding middle name of Kilbourne for him, and it was duly adopted. When Antoinette decided she needed a beach getaway, she had Walter buy a lot in the Malibu Beach Colony, as reported in the Times in May 1939. The year before, the Tullers had moved to the grand house built in 1912 by Dr. Peter Janss 455 Lorraine Boulevard in Windsor Square (later Norman and Buff Chandler's "Los Tiempos"). It was there that Walter Tuller died on September 27, 1939, with one paper giving its tribute the bold headline "MAJOR TULLER SUCCUMBS AT HOME IN L.A."

- Perhaps unsurprisingly, there was considerable ill will, so to speak, concerning the last will and testament of Walter Tuller. Within weeks of his death, a series of suits was filed by Edna May Tuller and daughters Lula May and Carol regarding Tuller's dissolution of a trust he'd set up for the young women's benefit, one that apparently included community property of their parents and of which perhaps Antoinette did not approve. Tuller had left his namesake and his daughter Carol $250 each and Lula May just $100 while the two younger children were left sizable trusts along with Antoinette. Lula May contended in her suit that her father had been controlled by the "keen mind, fascinating personality and compelling attraction" of her stepmother. On October 31, 1939, an item in the Times reported that 18-year-old Mary Louise Tuller had married theater doorman George Topper in Oakland 13 days after the death of her father. Meanwhile, perhaps having to adjust somewhat to the outcomes of her stepchildren's and her predecessor's lawsuits, Antoinette Tuller decided to unload 455 Lorraine and strike a deal with James Dickason for 555 Rimpau Boulevard in Hancock Park. With her two stepchildren gone from her household—Mary Louise married and Robert off to college and war service, after which he lived with his sister in Van Nuys—Antoinette Tuller appears to have been buying the 11-room 555 Rimpau more for a statement than a need for space. She kept it through the war years, selling it in 1945, buying the considerably smaller house at 132 North Las Palmas Avenue nearby, hiring Paul R. Williams, the house's original architect, to carry out some remodeling; she flipped 132 within a few years and, ever upward, would be moving on to Bel-Air. Apparently, however, she missed the old 'hood. In 1960 she bought the Lemuel Goldwater house at 627 South Hudson Avenue, retaining it until her death in 1974

- As nice as 300 South June Street might have been, it was on a busy corner with the Los Angeles Railway R-line streetcars grinding and clanging along Third Street to and from its terminus at La Brea Avenue, not to mention that in pre-freeway Los Angeles Third had become a major east-west automobile route. The climbing Antoinette Tuller wanted something grander and insisted on moving into 455 Lorraine Boulevard before—well before—any deal was made to dispose of 300 South June. Ads began to appear in the Times in September 1937: "FIRST TIME OFFERED—less than 1/3 original cost of $85,000." Ads a month later referred to the property as a "sacrifice" and noted that the "entire house is soundproofed," a hint that this was no quiet corner. With no buyers coming forward, the Tullers rented 300 to Virginia-born insurance man Thomas Garland Murrell, his wife Elinor, and their three daughters, who appear to have stayed until Walter Tuller's estate was finally able to sell the property in a tough wartime market after ads again appeared, these reading "Low price for quick sale." (After some years in Hillsborough, the Murrells would return to Los Angeles by 1951 to purchase 132 Fremont Place.) On June 4, 1944, the Times reported that 300 South June Street had been sold to building contractor and philanthropist Max Zimmer

- Born in Austria on April 15, 1893, Max Zimlichman arrived in New York in January 1914. A decade to the month later, after some years in Brooklyn and then working in the building trade in Warren and Cleveland in Ohio, he and his Russian-born wife Pauline, who had emigrated two years before her husband and whom he married in Brooklyn, settled in Los Angeles with their three daughters. Helen had been born in Brooklyn, Ruth in Warren, and Edith in Cleveland. It was in his December 1925 petition for naturalization that Max Zimlichman requested that his family's named be changed to Zimmer

- Max Zimmer got his start in building back in Ohio by talking a Warren shoe-store owner into remodeling his storefront; skeptical that it would improve his business, the owner had only to offer remuneration to Zimmer if he felt a positive effect on his trade. Zimmer's ploy worked. In California, he began building apartments in Boyle Heights but was soon specializing as a developer of commercial and industrial properties including large-scale supermarket projects in Pasadena, Lynwood, Redondo Beach, and in west Los Angeles, a major undertaking there being Marketville, the sprawling center once at Third Street and Sherbourne Drive. In 1952 Zimmer became head of the Rassco Development Company, which planned planned large-scale housing and manufacturing projects in Israel. That year he was involved in plans instigated by Hyman and Emma Levine of 428 South June Street to build a new Mount Sinai Hospital, with which he had been involved since its days as a clinic in Boyle Heights. He is credited with having built as many as seven temples and synagogues in the Los Angeles area and was a major philanthropist actively involved in the regional division of the Zionist Organization of America, the Los Angeles Jewish Federation, the University of Judaism, and the Jewish Home for the Aging in Reseda. Zimmer was instrumental in the formation of the University of Judaism (now the American Jewish University in Bel-Air), which recognized him on his 100th birthday by granting him an honorary doctoral degree. He was quoted in 1996 as saying that age would not keep him from enjoying his weekly cigar: "Take that away from me, I'm going to die." And he wouldn't until January 10, 1999 at 105. A fascinating two-part oral interview with Max Zimmer conducted in January 1973 can be heard here

- Helen Zimmer was married to real estate man Nathan Krems, who worked with his father-in-law in property development. The Kremses lived with her parents from early in their marriage, the family remaining at 300 South June into the 1970s. The Zimmers and the Krems did seriously consider moving out of the house only five years after moving in; the property appeared on the market in February 1949 priced at $55,000 and was still for sale as late as April 1951. Pauline Zimmer died on December 4, 1978, just shy of her 82nd birthday. Helen Krems died at 63 on November 10, 1980, after 300 South June had been sold

|

A Passover seder at 300 South June Street, circa 1952: Pauline and Max Zimmer are at the head of the table, with Helen and Nathan Krems standing to their right. |

- Succeeding the Zimmer/Krems clan at 300 South June Street by 1974 were Leopold (Lee) and Barbara Marks, who remained until his death in 1990 and hers in 1999. The Markses added an 18-by-38-foot swimming pool to the property in 1979 and built a long six-foot-tall block retaining wall along Third Street and another wall along the south side of the lot

- 300 South June Street was on the market in the summer of 2000 asking $1,295,000; an estate sale of the Markses' possessions was held that August

- Owners of 300 South June since 2000 have carried out extensive interior and exterior renovations and upgrades