PLEASE SEE OUR COMPANION HISTORIES

AN INTRODUCTION TO HANCOCK PARK IS HERE

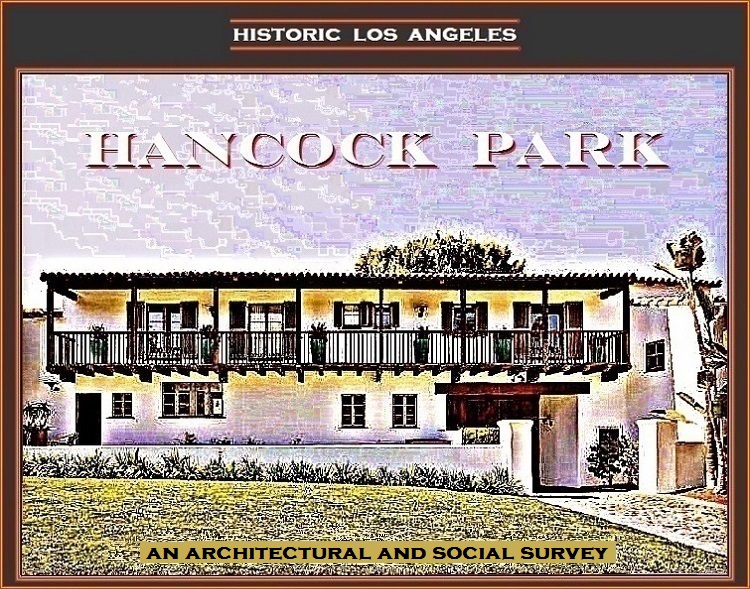

159 Hudson Place

- Built in 1935 on Lot 371 in Tract 8320

- Original commissioner: dress manufacturer Anees B. Malouf

- Architect: Ray J. Kieffer

- On October 17, 1935, the Department of Building and Safety issued A. B. Malouf a permit for a big two-story, 14-room residence with attached garage rather crammed onto a small corner lot at the northwest corner of Hudson Place and West 2nd Street. An item in the Los Angeles Times on October 20, 1935, noted that Ray J. Kieffer's design had been completed and that work on the building was to begin shortly

- Members of the Malouf family arrived in Los Angeles from Syria via Salt Lake City by 1928 to establish themselves as dress manufacturers in what is today called the Fashion District. By 1935, A. B. Malouf—a.k.a. Ernest, who'd arrived in 1933—and his brothers Bert and William ("Billy") had decided on a new mode of operation; rather than selling wholesale to random retailers, they would rebrand their dress manufacturing companies as "Mode O'Day," setting up retail franchises by that name to which to sell their inexpensive garments directly. There would eventually be more than 800 outlets in 30 states, with stores as far north as Anchorage. The first Mode O'Day shop opened on Brand Boulevard in Glendale catering to the likes of Mildred Pierce, at least before Mildred made her fortune selling pies. (Interestingly, in the 1945 film version of James M. Cain's 1941 novel Mildred Pierce, her daughter Veda had a nose when it came to affordable ladies' wear. After her mother gave her a seriously ugly party dress, Veda opined that it was made of "awfully cheap material. I can tell by the smell.") The Maloufs prospered in the way of hardworking immigrants, so much so that they were successful even in the depths of the Depression, rewarding themselves with substantial Hancock Park residences, among the very few big houses built in Hancock Park or elsewhere at the time. In 1933 Bert Malouf and his wife Marion and Bill Malouf and his wife Victoria—the wives, née Nassour, were sisters—built 101 North McCadden Place and 170 South June Street, respectively, both designed by Robert Finkelhor. The Nassour sisters' parents moved into 314 North McCadden Place in 1934 and would, four years later, relocate to 207 South Hudson Avenue. Ernest Malouf and his wife Mima decided to join the clan when, after first occupying 435 North Las Palmas Avenue, they built 159 Hudson Place in 1935, which they would retain for over 50 years

- Ernest Malouf began to develop real estate and invest in gold mining in addition to his duties as president of Mode O'Day. In the fall of 1943 Ernest, Billy, and Bert Malouf were sued along with other investors, among them Paul T. Sunday, son of sensationalist evangelist Billy Sunday, over a Burbank housing development scheme in which the group was accused of conspiring to realize unlawful profits. The Times of November 10 reported the decision against the Maloufs and their coinvestors and the order for each of the seven defendants to pay the 2023 equivalent of $558,000 in damages. Perhaps to the investors it was the cost of doing business; Mode O'Day was still manufacturing carloads of its cheap, colorful dresses when the firm was acquired by a retail-chain conglomerate in 1961, which continued the brand

|

| As advertised for sale in the Los Angeles Times, January 4, 1998 |

- Ernest Malouf and Mima Malouf—their familial relationship, if any, is unclear, though interestingly they appear to never to have had children—were both residents of Salt Lake City when they were married by a justice of the peace in Pocatello on July 9, 1919. Once their residential pinnacle had been achieved when they moved into 159 Hudson Place by early 1936, Ernest tended to business and became involved in local Republican politics while Mima tended to the house and did volunteer work, sometimes hosting events at 159. Two weeks after the permits for 159 Hudson Place were pulled in 1935, the Maloufs were robbed of $1,000 in furs and tapestries while still living on Las Palmas Avenue; at 159 on March 16, 1959, the Maloufs suffered another home invasion. While watching television with their housekeeper, Jean McKenny, that evening, two men rang the doorbell asking to use the telephone, claiming their car had broken down. Tearing out the phone line rather than using it, the bandits pulled out revolvers and, sounding like characters in a '30s melodrama (per the Mirror and the Hollywood Citizen-News), stated the obvious to the victims: "This is a stickup. Everybody keep quiet and no one will be hurt." While one man held a gun on the Maloufs and Miss McKenny, the other ransacked the house and found no jewelry, which was they had apparently been led to believe was somewhere in the house. Frustrated, the intruders angrily rejected an offer of the small amount of cash on hand when they spotted the nine-caret $12,000 diamond ring on Mrs. Malouf's finger and snatched it. The three victims were then pushed into an upstairs closet, a heavy bureau then pushed in front of it. It is unclear as to whether the robbers or the ring were ever found

- Ernest Malouf was still living at 159 Hudson Place when he died at the age of 82 on June 14, 1972. His widow appears to have retained ownership until her death 15 years later. Not long after Mr. Malouf's death, his former secretary—she had worked for him for six months—was charged with having stolen $315,000 worth of municipal bonds from his safe deposit box in April 1972. The prosecution claimed that 28-year-old Ellen Mae Dix of Woodland Hills had accompanied her aging boss to the Toluca Lake branch of the Bank of America to clip coupons and managed to slip the bonds into her coat. Her lawyer contended that the bonds were a gift and that the childless Malouf had developed a fondness for Dix, and that she was his third cousin who grew up in Hancock Park near the Maloufs and who was in the habit of referring to Ernest as her "uncle." Convicted of conspiracy, bank larceny, and possessing stolen property, she was sentenced to three years in federal prison; her co-conspirator, a Palos Verdes man who'd had a plan for selling the bonds under an assumed name, received three years' probation and 40 days in jail

- Advertised as a probate sale with an asking price of $1,450,000, 159 Hudson Place was on the market, furnished, six weeks after the death of Mima Malouf at the age of 87 on May 31, 1987. It was still on the market in February 1988 when ads touted its Steinway grand and "elegant Louis XV style furnishings," which, alarmingly, were apparently in every room. Such an extravagant mode would have been in accordance with the Malouf's choice of a heavy-handed exterior design back in 1935, which in those lean years would have been considered less than subtle. (The house, in fact, appears at first glance to have been built in the rococo 1980s)

- A number of names have been associated with 159 Hudson Place since 1987. It was on the market in late 1997 and early 1998 for $2,300,000. A sale for $5,850,000 was reported in June 2007. It came on the market in October 2018 for an ambitious $9,850,000, which by July of the following year had been reduced by well over a million to $8,533,000

Illustrations: Private Collection; LAT