PLEASE SEE OUR COMPANION HISTORIES

AN INTRODUCTION TO HANCOCK PARK IS HERE

101 North Hudson Avenue

- Built in 1928 on a parcel comprised of Lots 345 and 346 and the southerly 10 feet of Lot 347

- Original commissioner: private investor Gerald Crozier Young

- Architect: Roland E. Coate

- On May 2, 1928, the Department of Building and Safety issued Gerald C. Young a permit for a three-story, 32-room residence with an attached garage at 101 North Hudson Avenue; curiously, later alteration permits would variously cite room counts of 18 or 20

- Gertrude Kerckhoff married Azusa orange grower Gerald Young in a small ceremony at St. John's Episcopal Church on Adams Street on December 23, 1918; his father, William H. Young, was a veteran citrus rancher. The bride was one of the twin adopted daughters of lumber and utilities executive William G. Kerckhoff, who in 1908 had built 734 West Adams Boulevard, which still stands there. It seems that Gertrude and her sister Marion maintained an affection for the English-style house they grew up in, even if by the time it came to having their own residences they wouldn't have been caught dead living in increasingly déclassé West Adams. Marion married Webster Balkwill Holmes, vice president of the Southern California Gas Company, bank director, and oil investor, a year ofter the Youngs' wedding. Though twins tend to do things together, the young matrons, though not in total lockstep, decided to build impressive half-timbered houses in the same year in Hancock Park, one of the chief new developments attracting affluent migrants from the fading West Adams district. The sisters hired different architects but both would choose the same street on which to build new residences, which remain among the grander in Hancock Park, in 1928. Marion and Webster Holmes's 365 South Hudson Avenue, three blocks south of the Youngs' site, was started six months before construction began on 101 North Hudson

- Gertrude and Gerald Young would have three children. Louise was born on February 12, 1920, and William Kerckhoff on December 20, 1922. By the time Gerald Jr. arrived on February 1, 1925, the family had moved into the city, first renting 678 South Harvard Boulevard before taking a house in Beverly Hills. Gerald had assumed a position at the Southern California Gas Company in the employ of his brother-in-law. Reputedly having become Southern California's first junior tennis champion in 1903, the sport became a lifelong passion; Young served as president of the Southern California Tennis Association from 1932 to 1954. The new house on Hudson Avenue would include a tennis court. Young's business activities would involve private investing, perhaps of his wife's money, in addition to citrus ranching

- The more restless Kerckhoff twin seems to have been Gertrude Young; while Marion Holmes down the street would remain married and at 365 South Hudson for three decades, Gertrude wasn't as content with her husband. On July 29, 1935, the Times reported that she had taken a house for the summer at Lake Tahoe—specifying the Nevada side—to which she took the children. "Mrs. Young plans to be gone for six weeks...," a subtle indication that she was establishing residency to obtain a divorce. The decree came down in Reno on October 4. The Times referred to Gerald Young as a "clubman and tennis player"—perhaps indicating that for him pleasure took precedence over office life—while, it seems, Gertrude had her own preoccupations. On October 23, 1937, Gertrude married Hollywood real estate broker Eric Lindquist in Santa Barbara. Marion and Webster Holmes were the couple's only attendants. The Times of October 31, 1937, quoted the bride: "We've been friends for six months but decided rather suddenly to be married, Mrs. Lindquist laughed." The reporter added that the Lindquists would be making their home at his relatively modest 517 Avondale Avenue in Brentwood, though, true to form, he would be settling in with Gertrude and her three children at palatial 101 North Hudson Avenue. (By 1940 Gerald Young, who never remarried, was living with his parents, ages 85 and 72, at 2441 Mandeville Canyon Road in Brentwood, which was referred to in his Southwest Blue Book listing as "The Sycamores")

|

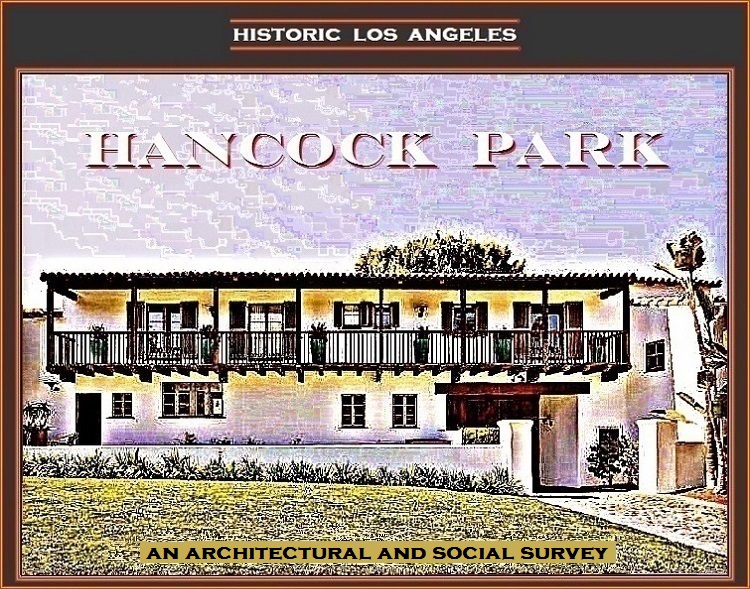

| The Kerckhoffs were just the sort of family the writers of television's Perry Mason seemed to love to feature—spoiled heirs and heiresses. Blaring headlines regarding Gertrude's high-living first cousin Stephens Kerckhoff's marital complications had predated her own by a decade; he had grown up at 1325 West Adams Street, which his father Herman, William G. Kerckhoff's 11-years-younger brother, had built in 1899 (and which still stands). One of the Kerckhoffs' TV-world cohorts lived at Fourth and June streets, where Perry asked Paul Drake to meet him while working on a case. The house depicted onscreen wasn't actually at that corner, but rather was 101 North Hudson, as seen above in a screenshot from the 1961 Perry Mason episode "The Case of the Torrid Tapestry." |

- The newlywed Lindquists were honored with a dinner by her widowed mother—William G. Kerckhoff had died in 1929—at 734 West Adams Boulevard on December 14, 1937. Guests included Richard Jewett Schweppe and his wife, née Annis Van Nuys, who were living at 165 Muirfield Road in Hancock Park; the Schweppes and her sister and brother-in-law, the James Rathwell Pages, who also attended Mrs. Kerckhoff's party—they lived at 354 South Windsor Boulevard in Windsor Square—would have probably been fascinated by revisting the tattered West Adams district, all but abandoned by their Old Guard cohort for Hancock Park, Windsor Square, and other more up-to-date suburbs. In February the Lindquists left on a European trip, which included a visit to Sweden to introduce Eric's new wife to his father; the couple didn't return to the States until April 28

- By the spring of 1941 the wheels were coming off the Lindquist marriage. On April 24 Gertrude filed suit against Eric on grounds of cruelty; per the Times the next day, she had kicked him out of the house three weeks earlier and was claiming that from the time of the marriage to the separation he had "treated her in a manner which caused her mental anguish and impaired her health," fairly standard charges. Ginning things up later in the year, Gertrude added to her complaint that Eric had told her soon after their wedding that he had only married a woman her age because she was rich, "and from then on he attempted to gain control of [my] funds and her property." The Daily News reported Mr. Lindquist's inevitable denial of the charges: "It was at her insistence, he declared, that he had paid off debts incurred before their marriage and had sent money to his relatives in Sweden." In a plea for him to be awarded alimony of $500 a month, he stated that her charges "had so upset his health that he is in no position to maintain himself in the manner to which he became accustomed following the marriage," this despite the Times having been reporting with some regularity on his success in selling real estate. He claimed that Gertrude objected to his working during the marriage. His countersuit included charging her "with climaxing a treatment of 'extreme cruelty' by insisting upon his entering a sanitarium for alcoholics although she knew that he was not an [sic] habitual drinker and not in need of any cure." "Lindquist stated he and wife had traveled through northern Europe since [their marriage] and in order to fight her suit properly he needs $500 from her for court costs to pay for taking of depostion testimony abroad." He also wanted Gertrude to pay his $10,000 attorney fees.

In October 1941 Eric added fuel to the media fire by alledging that his wife had received letters, telephone calls, and presents from former suitors; he claimed that his wife had developed a "preference" for a Viennese baron. Meanwhile, the Citzen-News reported that Gertrude, a "middle-aged heiress," had asserted in court that she believed her husband "made two mistakes after their wedding, the first being that he admitted marrying her for her money and the second that he "made it a habit to expound to her reasons why men were justified in murdering their wives." Things dragged on luridly. In February 1942 Judge William S. Baird of the the Superior Court issued a restraining order to keep the Lindquists "from annoying or molesting each other" and even ordered them not to speak to each other at all. The Citizen-News reported that Judge Baird intoned with a straight face that Eric could speak to the couple's English bulldog, "Pooch," who was in Gertrude's custody. (Also amusing is that the paper for some reason referred to Lindquist as a "one-time Swiss riding master.") Finally figuring out that Gertrude was no pushover, hapless cad Eric finally capitulated "at the 11th hour." A coda in the Times on March 28 was headlined "Mrs. Lindquist Gets Uncontested Divorce": "Like a soap bubble under pressure"—soap being the operative word, as in opera—"the bitterly contested divorce suit between Mrs. Gertude Kerckhoff Lindquist, lumber heiress, and Eric Gustave Lindquist, real estate man, dissolved yesterday in her favor following a 15-minute hearing" Eric went on to marry a hospital head nurse, his third wife, in 1946. Gertrude immediately dropped his name and was henceforth known—apparently until her death in 1989—as Mrs. Gertrude K. Young

- It appears that Gertrude Young went in for apartment living after leaving 101 North Hudson Avenue by early 1948, eventually settling at Park La Brea

- Gertrude Young appears to have sold 101 North Hudson Avenue to hotelier E. William Benson in 1947; Benson owned, among others in the Midwest, hotels in Indianapolis and Minneapolis and had bought the Park-Wilshire Apartment Hotel at Wilshire and Carondelet in Los Angeles two years before. In September 1948 Benson acquired the Voltaire Apartments on North Crescent Heights Boulevard from real estate man Roy Wendell Stovall and his wife Vida in a transaction that appears to have involved the transfer of 101 North Hudson to the Stovalls. The Stovalls didn't move into the house themselves, instead taking a house at 500 Perugia Way in Bel-Air, apparently purchased at auction; 101 became the home of Roy's elderly father, Thomas L. Stovall, and Roy's widowed sister Geneva S. Baugh and her daughter Frances. Like many real estate operators, Roy Stovall's own homes were commodities. Classified advertisements offering 101 North Hudson Avenue for sale began to appear in the Times in April 1950. One version called the house "One of the most impressive English Manor homes in Hancock Park" and went on to describe the property in some detail: "Beautiful entry & living rm. with light oak carved wood paneling. Large paneled den, 5 master bedrms. & 4 modern baths. Dressing rms., sitting rm. up. Ample servants' qtrs. House carpeted thruout with the finest wall to wall carpets. Beautiful landscaped corner lot, private rear garden & tennis court. Property can be purchased at a fraction of original cost incl. carpets and draperies or will sell fully furnished." On January 7, 1951, the Times ran a sizable image of the house with a caption stating that Mr. and Mrs. Thomas W. Simmons had just bought it "for a reported consideration of $100,000" from Mr. and Mrs. Roy Stovall of Bel-Air." That same day a large display advertisement appeared in the Times offering the furnishings of 101 at auction that afternoon

- Thomas Wyatt Simmons, an industrialist in the oil industry and racehorse owner, and his wife née Mabel Crosland would have only a short stay at 101 North Hudson Avenue. Mrs. Simmons had married her first husband, Louis Thompson, a Kern county oil man, in 1907 at the age of 21. After divorcing him Mabel, now 35, married 72-year-old San Francisco attorney Henry Ach in June 1922; he died three years later. The Simmonses were married in 1929, first renting 84 Fremont Place before buying 636 South Plymouth Boulevard in Windsor Square. Before buying 101 North Hudson, the Simmonses were living at their 400-acre Suzy Q thoroughbred ranch in La Puente. After little more than a year at 101, Simmons died of a sudden heart attack at home on the afternoon of May 20, 1952. Accustomed to visiting the Hollywood Turf Club—he had been chairman of the board for the past two years—he had only a few days before presented an award to Johnny Longden commemorating the jockey's 4000th winning ride

- Mabel Crosland Thompson Ach Simmons put 101 South Hudson on the market soon after the death of her husband and moved to the more manageable 315 Muirfield Road in Hancock Park. (In September 1956 Mabel married yet again, taking gift-shop owner and interior decorator Theodore "Dore" Fouch as her fourth husband.) By January 1953, the Edward S. Halls were owners of 101

- Mr. and Mrs. Edward S. Hall threw a black-tie housewarming party at 101 North Hudson Avenue on March 21, 1953; Mr. Hall was an insurance executive representing Mutual of Omaha in Southern California. A Mrs. Hall was still listed at 101 in the 1973 Southwest Blue Book; "Mrs. Hall" is cited as owner of the the property when the Department of Building and Safety issued a permit for a kitchen remodeling on May 10, 1974, although a Scott Sheridan, later of 455 North Las Palmas Avenue in Hancock Park, appears at 101 North Hudson in the 1973 city directory

- In September 2020 101 North Hudson Avenue was purchased for $11,500,000. After a thorough renovation, one of a typically lavish though anodyne sort suggesting that a flip was the aim, the property appeared on the market in January 2023 with an asking price of $23,995,000. Real estate interests in recent years have endeavored mightily to promote much more suburban Hancock Park as an "estate" area to compete with Westside districts; the ploy seems to be working for now, the New York Post reporting in 101's case on January 24 that a bidding war had begun for its flat, rather un-private central Los Angeles corner parcel. The renovation process involved the demolition of the property's tennis court, apparently Gerald Young's original, added a rear balcony, perhaps predicitably a trendy pickleball court, and a new 52-by-22-foot swimming pool