PLEASE SEE OUR COMPANION HISTORIES

AN INTRODUCTION TO HANCOCK PARK IS HERE

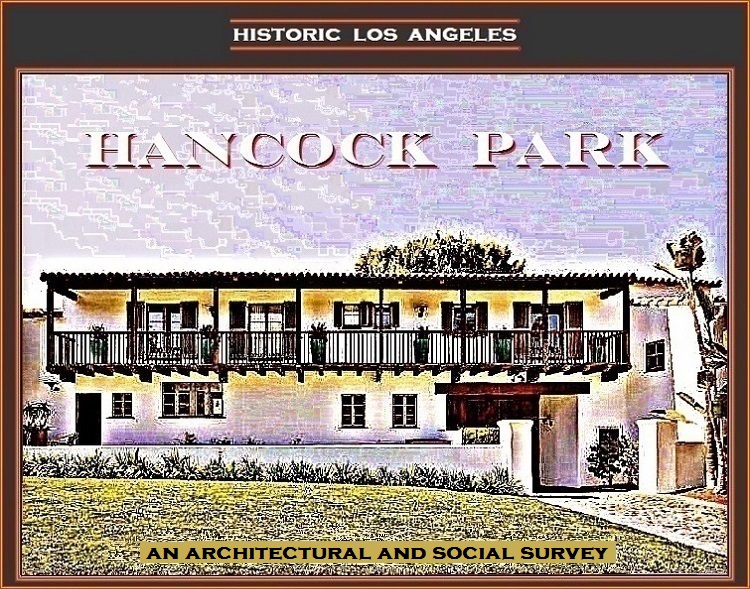

172 South McCadden Place

- Built in 1928 on Lot 165 in Tract 8320

- Original commissioner: real estate developer Marks & Gage (Victor Marks and John W. Gage) as a speculative project

- Architect: Don Uhl

- On April 10, 1928, the Department of Building and Safety issued Marks & Gage permits for a two-story, 10-room residence and a one-story, 20-by-30-foot garage at 172 South McCadden Place

- Among a significant number of other houses in Hancock Park and elsewhere in Los Angeles, architect Don Uhl designed 461 North McCadden Place, nearly identical to 172 South McCadden; building permits for 461 were issued to Marks & Gage in November 1928. Construction on another Uhl/Marks & Gage collaboration at 333 South McCadden Place, a center-hall design also similar to 172, began in early 1929

- Frances Blake Milbank, who'd been widowed by real estate and oil-field developer Nichols Milbank in April 1927, bought 172 South McCadden Place once it was completed, if not before

- On July 15, 1929, the Department of Building and Safety issued Mrs. N. Milbank a permit to add a bath upstairs at 172 South McCadden; Marks & Gage was the contractor for the work. While the document is unclear, Mrs. Milbank was issued a permit on September 29, 1936, to either completely replace the original one-story garage with a two-story building, or to add a second floor to the original; the resulting structure, still in place, included an artist's studio with a fireplace. Mrs. Milbank had been listed as an "Illustrator Designer" in the 1900 Federal census taken in Montclair, New Jersey; subsequent censuses list her occupation as "none"

- Frances Milbank was moving to Hancock Park from 671 Wilshire Place, which had been purchased by Nichols Milbank's first cousin Eleanor Milbank Anderson Tanner soon after its completion in late 1906 and, after she left circa 1915, occupied by Nichols and Frances, their sons Morris and Nichols Jr., and daughter Mary Frances. Cousin Eleanor's super-sanitary house at 671 Wilshire Place was specially retrofitted to indulge her extreme over-protection of her daughter Betty, called "The Human Orchid" by the press—Eleanor would not even let Betty's father kiss her; not surprisingly, divorce ensued, Eleanor later suffering a nervous breakdown and moving back east. (Eleanor's brother Jeremiah Milbank Anderson had died of diphtheria at the age of seven.) Nichols Milbank was the brother of Isaac Milbank Jr., who had been vice-president and general manager of the New York Condensed Milk Company, founded in 1858 by his uncle Jeremiah Milbank (who supplied the capital) and Gail Borden (who supplied the science) and later, as the famed Borden Company, progenitor of Elsie the Cow. In October 1886 Nichols went to work for New York Condensed Milk alongside his brother and would remain with the firm until following his brother west to California. Ties between the Milbank and Borden families were tight. Of Gail Borden's daughter Philadelphia Borden Johnson's seven children, one son was named Milbank after his grandfather's business partner and a daughter, Virginia, would marry Isaac Milbank Jr. It was Milbank Johnson, who became a prominent Southern California physician, and his older brother Gail Borden Johnson who had first arrived in Southern California circa 1890, soon setting up a shoe manufacturing business in Alhambra. By some accounts for reasons of his health, Isaac and Virginia began to visit California frequently after the turn of the century, often being mentioned in newspaper accounts of social events. It wasn't until after the January 1905 death of their firstborn son, Lawrence—Nichols's nephew—that the Isaac Milbanks Juniors decided to move west permanently. In May 1905 they bought 2607 Wilshire Boulevard, a few blocks east of Wilshire Place, as well as additional lots in Gaylord Wilshire's Wilshire Boulevard Tract. On one of these was built 615 South Coronado Street, which Nichols Milbank purchased after moving his family west from Montclair, New Jersey, in March 1906. (This residence would be retained by Nichols and converted into a rooming house for revenue after he moved to Wilshire Place)

- Rather famously it was Midwesterners who came to Los Angeles and who became known for their skills at urban development, in terms of the built environment as well as socially. The Old Guard Milbank family was a rare extended tri-state New York clan who out west upped the ante socially and would contribute as well to the development of their adopted city. As part of a syndicate, Isaac Milbank bought a 35-acre tract a few blocks north of his Wilshire Boulevard property that was developed into Upper Rampart Heights. Assimilating into "come one come all" California with ease, Isaac Milbank assumed a business and social position as though to Los Angeles born. While of Baptist heritage, in Los Angeles Milbank worshipped among his ruling-class equals at St. John's Episcopal Church on Adams Street. He became a booster of aviation in the Southland and, just before his death at 58 in August 1922, was a member of the investment group that developed the Biltmore Hotel. He was a member, naturally, of the California, the Athletic, the Los Angeles and Wilshire Country clubs, as well as of the very selective Bolsa Chica Gun Club. Over the years, he would become a director of the German-American Trust & Savings Bank (Guaranty Trust & Savings after April 1917) with his brother-in-law Gail B. Johnson and Joseph Burkhard of Pacific Mutual Life Insurance and Union Oil as well as an investor in the California Delta Farms and Sinaloa Land development projects with Lee Allen Phillips, among other power brokers

- Isaac Milbank's roost in Gaylord Wilshire's original tract lasted eight years. Clearly enjoying his role as a builder of Los Angeles, Isaac was inspired when the opportunity arose to acquire the property occupied by the Los Angeles Country Club prior to opening its present Westside clubhouse in 1911. Platting of streets and building on the rolling plain bounded roughly by 10th Street (now Olympic Boulevard), Pico Street (now Pico Boulevard), Western Avenue, and Crenshaw Boulevard began even before the club vacated the district to which it bequeathed its legacy, though a legacy little known today. Isaac Milbank hired architect G. Lawrence Stimson to build an extravagant new residence at 3340 Country Club Drive at the center of the area dubbed Country Club Park, to which his family moved in 1913 and which still stands, as does Milbank's Craftsman Santa Monica vacation house built two years before

- Nichols Milbank stayed at 671 Wilshire Place even as the boulevard three houses to the north began to be commercialized. Though he never lived in his uncle's subdivision, he was, in addition to his other development projects, president of the Country Club Park Company; he was serving as such and as treasurer of St. John's Episcopal Church when he died of a stoke in Paris on April 30, 1927. He was 60 years old and near the end of a three-month tour of Europe with Frances and Mary. On her return, Mrs. Milbank appears to have immediately made plans to leave 671, perhaps desiring not to live in it without her husband but more likely due to John G. Bullock's plans for his towering new department store for which 671 would be demolished in the spring of 1929, Bullock's-Wilshire opening that September. Perhaps under the gun and probably in no mood to search for a house and hire an architect and contractor, Frances Milbank chose the already built or abuilding 172 South McCadden Place in Hancock Park, deciding on that subdivision over Country Club Park, which, while luxuriously laid out, was not quite as fashionable as Hancock Park—it seems that after World War I the key to real residential fashion would be to live north of Wilshire Boulevard

- On November 27, 1929, Mary Frances Milbank was married to Eugene Lester Cutting Jr. of Modesto at St. John's Episcopal; a reception was held at 172 South McCadden Place

- Frances Milbank would remain at 172 South McCadden for the next 18 years. At St. John's at noon on June 21, 1938, in an event reported in Life magazine, she married the recently retired Episcopal Bishop of Nebraska, British-born Ernest Vincent Shayler of Omaha; he would be moving west and into 172 South McCadden. The Shaylers were still living there when he died, age 79—or 82, depending on the source—at Good Samaritan on June 25, 1947, after a brief illness; his remains were sent back east for burial alongside his first wife. Mrs. Shayler died in 1968 at the age of 95; she would be buried as Frances B. Milbank in San Gabriel Cemetery alongside her first husband

|

| As seen in Life magazine, July 4, 1938 |

- Frances Shayler put 172 South McCadden on the market within months of her second husband's death in June 1947; ads appeared in the Times that October touting, among other features, the knotty-pine studio space over the garage in which a faded child actress would later park her 1947 Lincoln Continental cabriolet

- 172 South McCadden Place sold soon after it was put on the market in 1947 to Edwin Wallace Ross, president of the National Silver Company. Born as Edwin Wallace Rosenbaum in Manhattan on December 19, 1912, he had moved to Los Angeles by 1930 with his mother and their new name after Mrs. Ross had divorced Emanuel Rosenbaum; they lived at first with her sister and brother-in-law as well as the sisters' father in a rented duplex on South Catalina Street. Edwin married Violet Levy in Los Angeles in February 1935; they were both 22. The Rosses were living in San Francisco when their son Robert Roger was born on March 28, 1939, but had returned to live in Los Angeles by the fall of 1940, living in rented accommodations until purchasing 172 South McCadden. The Rosses' daughter Karen Stephanie was born on Leap Day 1948 just as they would have been moving into the new house

- The Rosses appear to have lived quietly at 172 South McCadden Place through the 1950s. Edwin was just 47 when he died on March 13, 1960. Two years later, Violet would allow the Hudson sisters, Blanche and Jane, to move into 172 temporarily, creating one of Hollywood's most notorious film addresses

- The classic film Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?, released on Halloween 1962 and based on the 1960 novel by Henry Farrell, came to be made after producer and director Robert Aldrich persuaded Jack Warner, who was no fan of its faded stars (who were, perhaps needless to say, Bette Davis and Joan Crawford), to distribute the film through Warner Bros. When it came time to find a house for location shooting, Aldrich knew where to look—he had lived in Hancock Park himself, at 501 North Cahuenga Boulevard, during the 1950s, moving to the grander, arguably creepier 504 South Plymouth Boulevard in Windsor Square by 1956 and still living there during production of Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?. Finding a house for location shooting near Aldrich's home and studio base on Melrose Avenue would have been a consideration; it is unclear as to how Aldrich found and persuaded Violet Ross to allow exterior (and limited interior) filming at 172 South McCadden Place or how (or with how much) he may have negotiated with her and with Dr. Henry J. Rubin next door at 166 South McCadden for use of his driveway, or with other neighbors for the disruptions of the shoot. A partial re-creation of the exterior façade of 172 was built on a sound stage at Producers Studio, as were sets mimicking the interior with such odd Hollywood features as a bedroom door that opened outward to smooth blocking and camera work. While as creepy a story as was the pairing of two aging stars in an unflattering light—literally and figuratively—was initially thought to be, the completed film proved to be a hit, with the "Hudson house" immediately moving to the top of the list of local residences immortalized on film. (Though demolished by the time of Baby Jane's release, Norma Desmond's pile at 10086 Sunset Boulevard—a.k.a., 641 South Irving Boulevard in Windsor Square—was another.) A 1991 remake of Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? for television, inexplicably starring Lynn and Vanessa Redgrave, used nearby 501 South Hudson Avenue as the Hudson sisters' residence, though, curiously, a shot of 166 South McCadden Place appears in the 1991 film just before a cut to 501 South Hudson

- Violet Ross sold 172 South McCadden Place to real estate investor Basil L. Lustig and his wife Esther in 1964

- The Lustigs remained at 172 South McCadden Place until 1972; the property was being advertised for sale by that spring, with subsequent price reductions. With Hancock Park values at their lowest ebb since the war years after the civil unrest and Manson crimes of the '60s, the house lingered on the market until late summer

- Parking-lot operator and real estate investor Art Lumer and his wife Sara succeeded the Lustigs at 172 South McCadden Place. The Lumers would remain there for the rest of their lives; Mr. Lumer died in March 1997, his widow in June 2020

- On October 17, 1972, Art Lumer was issued a permit by the Department of Building and Safety for a kitchen remodeling; on November 10 of that year he was issued a permit to add an 18-by-40-foot pool to the rear of the back yard

- With Hancock Park property values vastly improved since the Lumers' 1972 purchase, 172 South McCadden Place was on the market in December 2020, asking $3,800,000. In the fevered COVID real estate market, it was reported sold almost immediately for $3,845,000, though building permits for work on the property as late as May 2022 list the owner as the Sara Lumer Trust

Illustrations: Private Collection; LAT; Life; Warner Bros.